Enigma converted plain-text into cipher-text by means of letter key depressions closing switches, completing circuits, and lighting lamps, one for each letter of the alphabet. The enciphering was achieved by virtue of the circuits being completed through the medium of a plug-board and three (selected from five, from December 1938) rotors each with 26 contacts per side. The contacts were connected internally such that, as the rotors turned, the completed circuits were different for every key depression. The different electrical circuit configurations numbered 158,000,000,000,000,000,000.

Polish Intelligence made the first inroads into breaking Enigma-coded messages, and Bletchley Park first broke into German Enigma ciphers in January 1940. Manual techniques however were outstripped by increasingly complex German military set-up routines for the machines. Alan Turing, a brilliant Cambridge mathematician, set about developing a machine to work out the relevant rotor, ring, plug-board and message selections and settings that would not be thrown by further German operational changes.

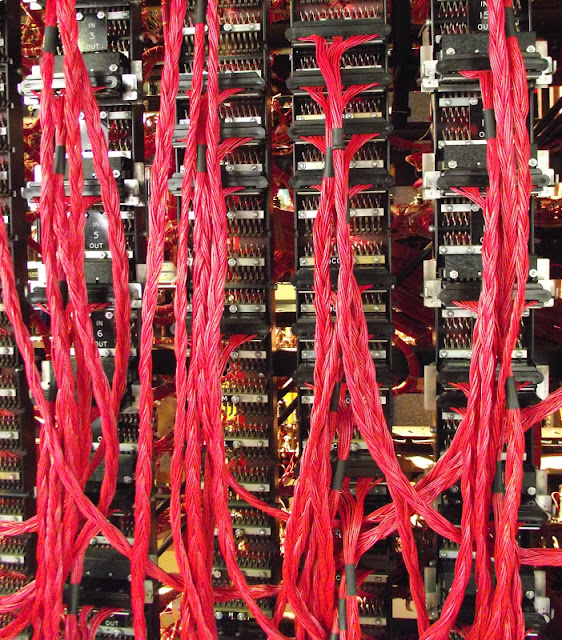

The Bombe, named after an earlier Polish machine used in de-encryption called the Bomba, itself reputedly named after an ice-cream, was built in just nine months and ready by March 1940. The machine made use of a 'crib', a known correspondence between a piece of cipher-text and the original plain-text, worked out from study of stereotyped messages, for example those commencing, "Weather report." In essence, the Bombe, each vertical set of three drums representing an Enigma machine (top), 'tested' the menus that were plugged up on the back of the machine (above) to reflect the crib.

A rotor order was chosen and an input letter selected. The Bombe worked through each possible rotor set-up, stopping each time a logical partner letter to the input letter was found. The resultant partial keys were tested on a Typex machine, modified to replicate an Enigma, to see whether the cipher-text would produce segments of German plain-text. Gradually, the rotor settings would be determined, such that ultimately all messages using that day's key could be decoded. Each day, the process had to start again.

At Bletchley Park, central to all this activity, is a fully working reconstruction of a Bombe. Entirely electro-mechanical, the machine is essentially a massive system of relays, emulating the rotor systems of 36 Enigmas. The design was continually improved, and by 1945 216 machines of various types were in use in the UK. Run 24 hours a day, without downtime for maintenance despite their 350 lubrication points (third photograph), the Bombes were incredibly robust. And proved absolutely vital to the war effort.

1 comment:

Turing's prototype Bombe was improved by the addition of Gordon Welchman's diagonal boards, introduced in August 1940, which served to reduce the number of false stops. A solved key enabled all messages sent via a given Enigma communications link to be deciphered, until the key for that link changed at midnight. Four-rotor Bombes were developed to cope with the four-rotor Enigmas introduced by the German Navy in 1942 for U-boat communications, producing a cipher known as Shark. These high-speed Bombes were further developed in the States, and first broke Shark in July 1943

Post a Comment